Buckle up, this is going to be a long one.

Of all the techniques found under the broad umbrella of ‘contact printing’, the gum-oil print is the one that has fascinated and captivated me most. Comparatively young, it was developed by renowned artist Karl Koenig in the 1990’s (a hundred and fifty years after most techniques I’ve played with), as a method of positive printing on large scales. For me, Koenig’s techniques are the foundation for an incredibly emotional and expressive printing method. When I first saw the contemporary work of Anna Ostanina however, I realized that the technique had met its pinnacle of refinement. Her huge format prints are an absolute triumph in the art form. It was in seeing these prints that I went from being fascinated and intimidated by the process to planning how I could do it justice by my novice hands.

So. What is it? Well for one, its a vehicle to explain the fundamentals of photochemistry in a weird and novel way that even I had a difficult time wrapping my head around for the first few times I read about it.

We are all familiar with the concepts of negatives and positives in photography. We are also usually familiar with the concept of photosensitivity, where a substance reacts to light. Usually photosensitivity causes a colour change (as in the case of silver nitrate where it turns black when exposed to light), but sometimes photosensitivity can evoke a change in structure rather than colour. This concept is the fundamental process in photography.

The main chemical that forms the basis of gum oil printing is Potassium Dichromate (or Bichromate). This stuff, rather than turning dark when exposed to light, becomes hard. In areas where it has been exposed to light, it forms a resist to the oil paint, stopping it from sinking in to the paper.

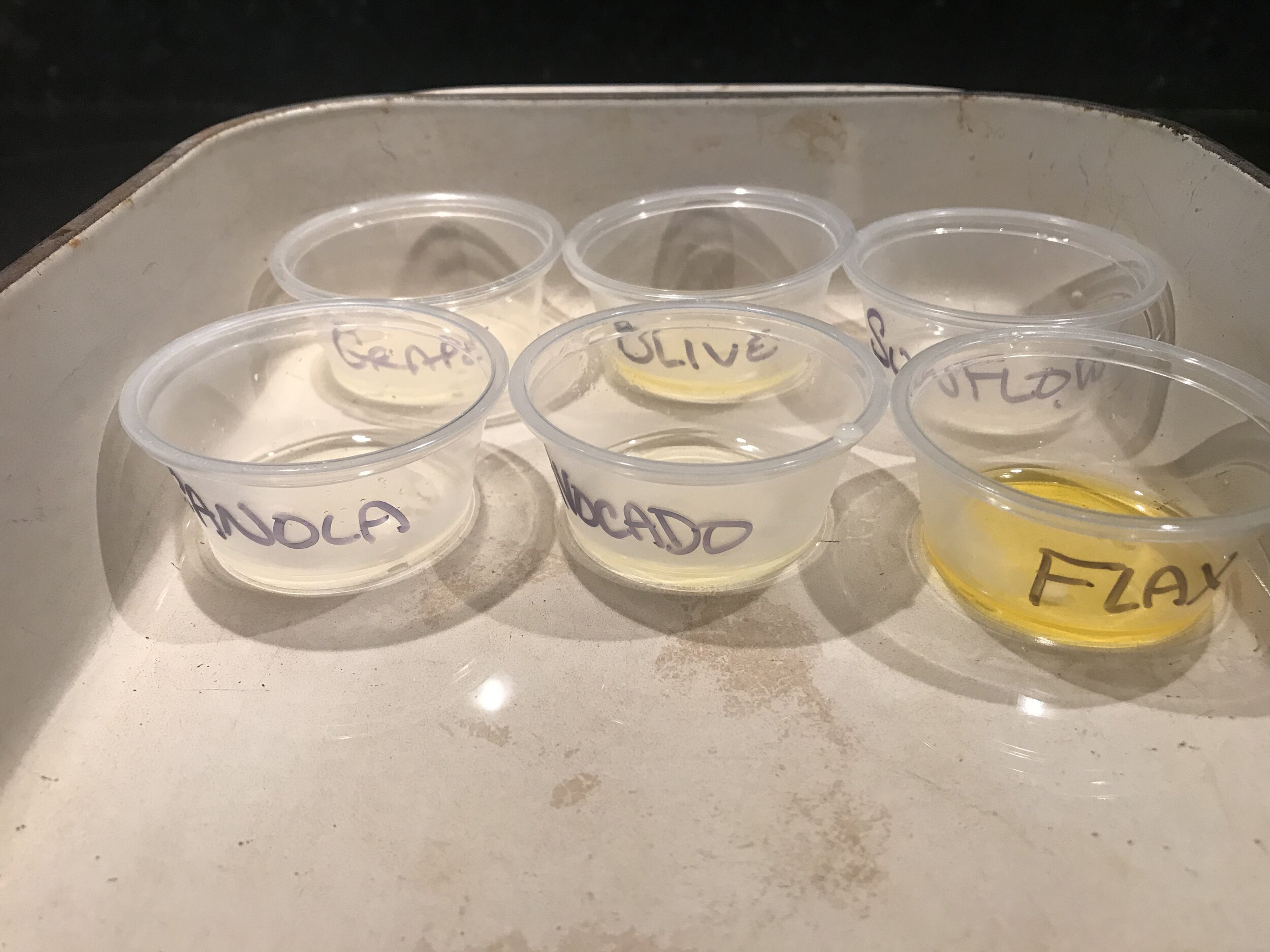

As usual with these new experiments, I first took stock of what materials I have, and which ones I need. Gum oil printing requires - as the name hints - oil paints. Being a bit frugal, I chose to make my own oil paints with stuff I had laying around. I tested a bunch of different oils (mixed with refined beeswax) as bases, and tried milling my own carbon pigment (no luck with that). But luckily I found some soap-making pigments that worked beautifully. Below are some tests for this process.

A note about Potassium Dichromate:

So naturally safety equipment is of the utmost importance. Luckily its really only the dust thats deadly - and once the dichromate is mixed with the support matrix its diluted to a point of being pretty safe (I mean, I wouldn’t go licking my final prints, but other than that they should be ok to handle).